In management research, we often ask the “so what?” question. So, a company implemented a new CSR policy. So, a firm invested heavily in IT infrastructure. Did it actually create value?

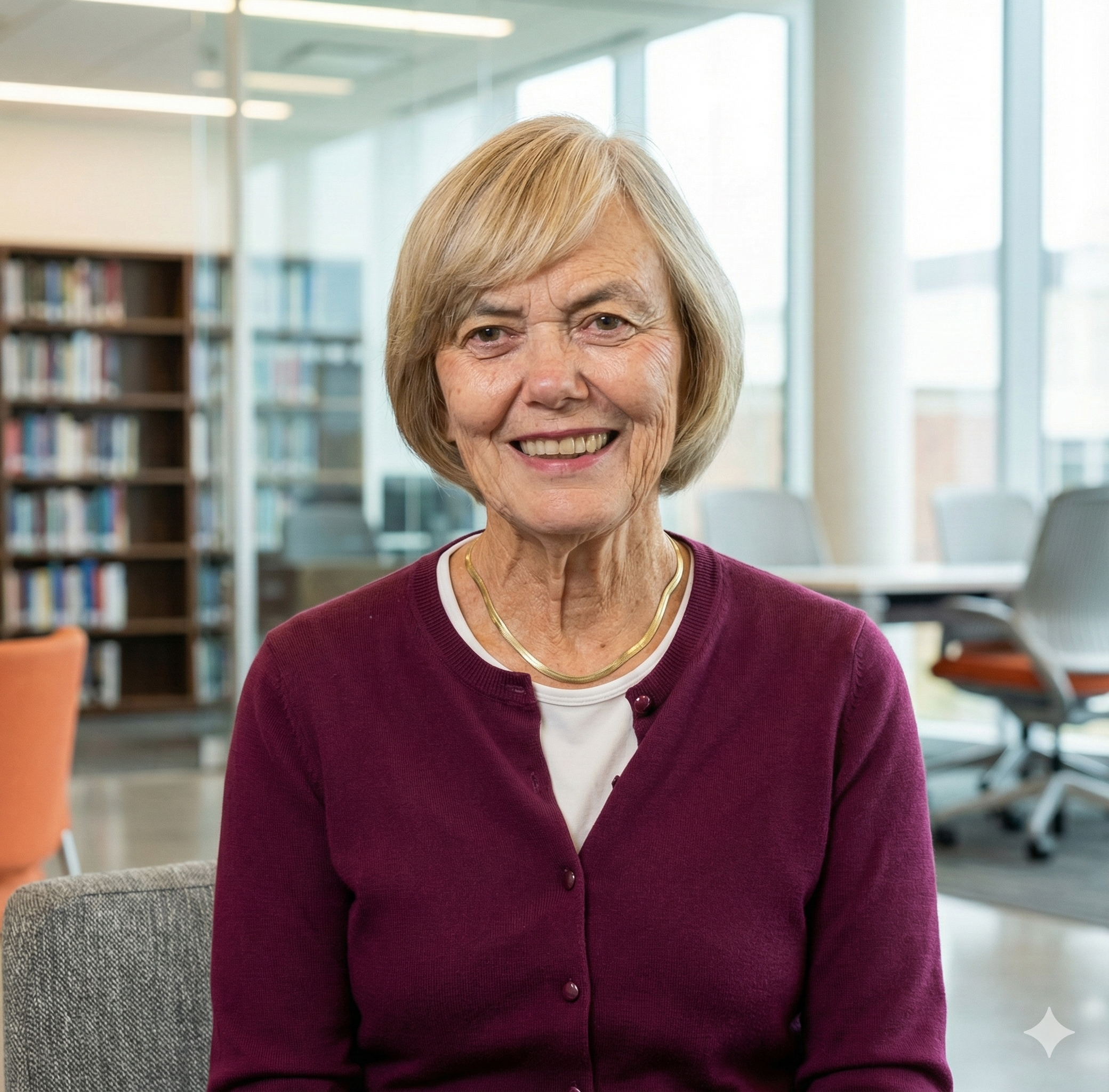

For decades, scholars have tried to answer this using Event Studies—a statistical method that measures the impact of a specific event on a firm’s stock price. However, in their seminal paper, “Event Studies in Management Research: Theoretical and Empirical Issues,” Abagail McWilliams and Donald Siegel exposed a critical flaw in the field: we were doing it wrong.

In this article, I break down their critique and their proposed “rules of the road” that remain the absolute standard for rigor in management and Information Systems research today.

The Core Theory: The Efficient Market Hypothesis

To understand McWilliams and Siegel, you must first accept the underlying assumption of event studies: Market Efficiency.

The theory posits that stock prices reflect all publicly available information. Therefore, when a new piece of information (an “event”) hits the market—say, a surprise merger announcement—the stock price should adjust immediately to reflect the market’s new valuation of the firm’s future cash flows.

If the market is efficient, we don’t need to wait months to see if a strategy worked. The immediate “abnormal return” (the difference between the actual stock price change and what we expected the stock to do) tells us the answer.

The 3 Critical Errors Researchers Make

McWilliams and Siegel reviewed roughly 30 studies published in top management journals and found them plagued by methodological flaws. Here are the three biggest traps they identified, which every PhD student needs to avoid:

1. The Problem of Long Event Windows

Many researchers try to capture the “full effect” of an event by using long windows (e.g., 30 days before and after an announcement).

- The Flaw: In a 60-day period, a major corporation will experience dozens of other events—earnings reports, legal disputes, macroeconomic shifts. It becomes impossible to say if the stock price moved because of your variable or something else.

- The Fix: Keep it tight. McWilliams and Siegel argue for a very short window (e.g., 2 days: the day of the announcement and the day after) to isolate the signal from the noise.

2. Ignoring Confounding Events

This is the “silent killer” of research validity. Imagine you are studying the stock market reaction to “IT Outsourcing Announcements.” You find a firm whose stock jumped 5% on the day they announced an outsourcing deal. Success, right?

- The Flaw: What if that same firm declared a massive dividend on the exact same day? The stock jumped because of the cash payout, not the IT strategy.

- The Fix: You must ruthlessly screen your sample. If a firm has a confounding event (dividend, merger, CEO change, government suit) during your event window, it must be dropped from the sample.

3. Lack of Theoretical Justification

Researchers often run event studies just to see what happens, without a solid theory explaining why the market should react.

- The Flaw: Without a hypothesis, you are just data dredging.

- The Fix: You must explain the mechanism. Why would this specific event alter future cash flows? For example, “CSR reduces long-term risk, which lowers the cost of equity, theoretically raising the stock price.”

Why This Matters for IS Researchers

As Information Systems scholars, we frequently use event studies to measure the value of IT. Whether it is the announcement of a new CIO, a data breach, or an investment in AI, the market’s reaction is a powerful proxy for business value.

However, the “digital” signal is often weak compared to general financial news. This makes McWilliams and Siegel’s advice even more critical for us. If we don’t control for confounding events and keep our windows short, the subtle impact of IT initiatives will be drowned out by the noise of the market.

Conclusion: Rigor is Not Optional

McWilliams and Siegel didn’t write this paper to discourage us; they wrote it to professionalize us. They taught us that finding “significance” isn’t enough—our methods must be robust enough to withstand scrutiny.

When designing your next research paper, look at your methodology section. Are you accounting for outliers? Have you checked for confounding events? Is your window justified? If you can answer yes, you aren’t just running numbers; you’re contributing to science.

Leave a Reply